Windows 11 has thrown a little known piece of hardware in the limelight, one that could potentially make or break the success of Windows 11. Meet the TPM.

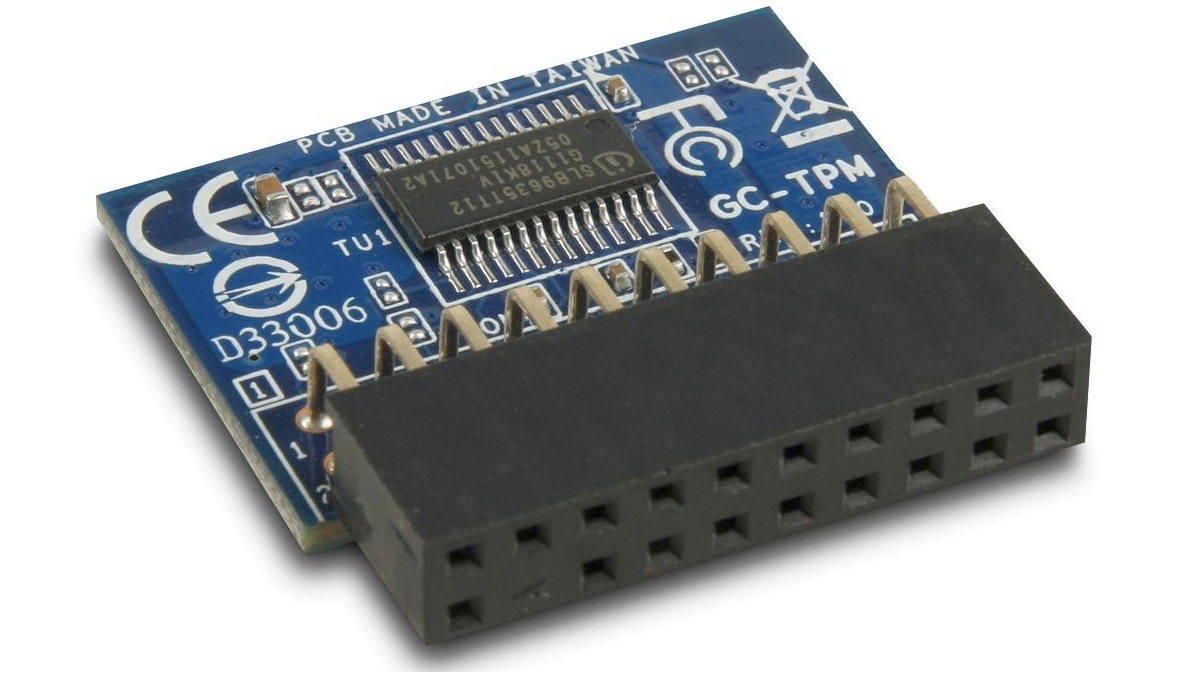

Its purpose is to protect your data (business or personal). TPM stands for Trusted Platform Module, has been around for almost a decade and it's a tiny bit of hardware - usually a processor (that's right a CPU) - that makes a big difference by protecting the data on a device.

Why a TPM?

Data protection is particularly important with laptops and tablets, because of course such devices are lost and stolen in huge numbers.

Each of those laptops is a data disaster waiting to happen, because laptops are often used to store sensitive or regulated data - HR records, perhaps, or financial data, or your top secret plans for global domination. If that data got into the wrong hands.

Enter TPM; TPM can be used to encrypt data so that even if it falls into the wrong hands, unauthorized users can't access it in theory.

TPM in action

A TPM-protected device requires its user to identify themselves. Depending on your systems, that identification can be accomplished in several ways: using a PIN code or a password, through bio-metric data such as fingerprints, via a smart card or a one-time password, or by a combination of those methods (note that this step usually happens before password managers come into play).

Whatever method you choose is the key to your system, and your data is safely locked away. TPM's job doesn't stop when the correct user is logged in. It can be used to encrypt the entire hard disk or just parts of it, it can authenticate online activities such as secure email and virtual private networking (VPN), and it can also be used to ensure that when a computer reaches the end of its life it doesn't go to the recycler/refurbisher with any confidential data still on it.

TPM, so hard to beat

TPM-based encryption is exceptionally difficult to break. TPM-protected data can't be read without the correct authentication, and because encryption keys are processed independently by the TPM processor, it isn't vulnerable to operating system vulnerabilities or software-based hacking attacks.

It isn't vulnerable to physical attack either. TPM-enabled devices can tell if hardware has been added or removed, and they can be configured so they'll refuse to operate if they detect such tampering.

You can't beat the encryption by removing the hard disk and putting it in another machine, because TPM-based encryption can only be unlocked from by the specific TPM processor that locked it away in the first place.

And even extreme measures such as transplanting the TPM chip into a different computer won't work, because the TPM processor is tied to the device it was first installed in.

Taken together, those features mean that the TPM offers businesses something very important: the knowledge that even if devices fall into the wrong hands, the data on them won't.

TPM and Windows 11

Windows 11 was announced on June 24 and came with a rather unexpected surprise, the presence of TPM 2.0 as one of the minimum requirements for setting it up. Given the fact that TPM is historically a business/enterprise feature, it is therefore less common in DIY, custom-built and boutique-sourced rigs.

Adding TPM, for many, turns out to be a doddle for whoever knows how to access a BIOS and enable Firmware TPM (or fTPM) but then again, your mileage will vary and for many, many users, that might mean having to either add a TPM module or buy a compatible Windows 11 PC when they come to the market.

As to why Microsoft made it compulsory to have TPM, well other than the security aspect, some might posit that doing so could make it harder, much, much harder for pirated/illegal copies/licences of Windows 10 to be sold in the open market.

from TechRadar: computing components news https://ift.tt/2TVWSed

via IFTTT

No comments:

Post a Comment